Beam of Light Coming From Persons Chest Fantasy Art

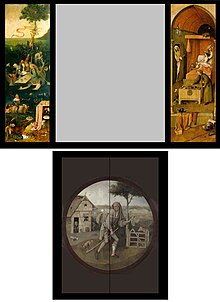

| Death and the Miser | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Hieronymus Bosch |

| Yr | 1490-1516 |

| Location | National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. |

Decease and the Miser (also known at Expiry of the Usurer) is a Northern Renaissance painting by Hieronymus Bosch produced between 1490-1516 in Northern Europe. The slice was originally part of a triptych, but the centre piece is missing. It is a memento mori painting, which is meant to remind the viewer of the inevitability of death and the futility of the pursuit of textile wealth, illustrating the sin of greed.

There is still fence about the exact symbolism of the man and the objects in the foreground. Bosch was influenced past the Ars moriendi, religious texts that instructed Christians how to live and die. Information technology is currently held in the National Gallery of Fine art in Washington, D.C.[ane]

Clarification [edit]

Death and the Miser belongs to the tradition of memento mori, a term that describes works of fine art that remind the viewer of the inevitability of death. The painting shows the influence of popular 15th-century handbooks (including text and woodcuts) on the "Art of Dying Well" (Ars moriendi), intended to aid Christians choose Christ over earthly and sinful pleasures.

The scene takes identify in a narrow, vaulted room that holds a human on his deathbed, similar to the unclothed, thin, and sickly representation of souls in other Bosch triptychs.[ii] The skeletal figure of Death emerges from a cupboard on the left with an arrow pointed at the dying human. An angel lays a hand on the human's shoulder, with a hand outstretched to the ray of light emanating from the window on the left, where a small crucifix also hangs. There is a nefarious fauna property a lantern peeking down from the canopy of the bed, while a "devil" offers the man a large sack of money.[2] These fantasy blazon creatures can be seen in many of Bosch's other paintings, most famously The Garden of Earthly Delights.

In the foreground, an old man dressed in green deposits coins into the sack of a demon in the body while gripping his cane and rosary in his left hand.[3] The trunk contains worldly possessions: a pocketknife, money, armor, a gold weight (that looks similar to a chess pawn), and envelopes, notes, or messages. Discarded garments and a winged demon figure are closer in the foreground, with other weapons and pieces of the suit of armor.[iii] The room is seen through a pointed archway flanked with columns, merely the foreground appears to be outdoors. Information technology is unknown what sort of construction the room is attached to, if any.

Bailiwick and Interpretation [edit]

Death and the Miser combines different timelines into a single scene. It depicts the final moments of human being called a miser, a hoarder of wealth, or an usurer, who gives loans while profiting from an often unfair interest charge per unit. It's widely accustomed that the quondam homo in dark-green is a slightly younger version of the miser, in full health, storing gilded in his coin chest (which abounds with demons) while clutching his rosary, indicating both his desire for piety and wealth.[three]

Usury was considered immoral and a great sin (a "sin against justice"[2]) in the early Renaissance period, mentioned specifically in the Bible in Luke 6:35, where Christ recommends free lending rather than profiting from the issuance of a loan. Medieval Church law followed these instructions and denounced usury as a practice and excommunicated members for information technology until the Quango of 1516 passed montes pietatis (mount of piety), which stated that charitable institutions were allowed to issue low involvement rate loans to the poor.[2] This law implies that usury was not often skilful, but the contrary is true, and many people, poor and well-to-do alike, could not survive without a loan at some indicate in their lives. It became so common that regime adult a modus vivendi, or agreement to peaceful coexistence, with pawnbrokers, then known as lombards (named afterward the region of their origin). It became so mutual and legal that they were regulated by regime until a more fair and stable public loan policy was established in 1618.[ii]

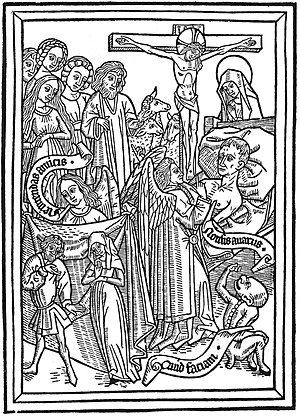

"Bona inspiratio angeli contra avariciam,", Cologne, woodcut from Ars moriendi, chapter 10, c. 1450.

The scene is highly reminiscent of an before illustration in the Ars moriendi where a dying man is cautioned virtually his avarice in chapters ix and x of the volume. In chapter nine, the man is tempted by avarice (greed) upon his deathbed, with his wealth shown by expensive treasures, like to the trunk at the foot of the bed in Bosch's painting. In chapter ten, an angel warns him of the dangers of avarice, telling the miser, "Protect yourself confronting the putrid and mortiferous words of the devil, for he is nothing but a liar… In the end everything he does is deceitful."[three] Here nosotros see the affections with 1 manus upon the miser's shoulder, lifting his other to the light of Christ, imploring him to brand the Christian decision rather than succumb to temptation and sin.[2] The crucifix in the window seen in the miser's room is likewise a fundamental feature of the Ars moriendi illustrations in these chapters, and reminds united states how separate and disparate Christ is from all of the worldly troubles and possessions depicted in the room below.[three] Fifty-fifty with the affections's intervention at his bedside, equally Decease looms, the miser's gaze and hand are directed downward, unable to resist worldly temptations, reaching for the bag of golden offered by a temping demon.[iv] Whether or not the miser, in his last moments, will encompass the salvation offered by Christ or cling to his worldly riches, is left uncertain.[5] This is in stark contrast to the Ars moriendi, where the angel successfully persuades him to embrace Christ. It implies that, rather than otherworldly creatures battling for the soul of a person, the decision lies in their own mitt and no 1 else's.[6]

Bosch's familiarity with the visual tradition of the Ars moriendi can as well exist seen in the top left roundel (pictured) depicting the death of a sinner in The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Concluding Things. There are several points of similarity, such as the figure of Death and the juxtaposition of an angel and devil at the headboard.[7] Death and the Miser could be Bosch's illustration of the sin of avarice, intended to be a part of this series, meant to depict each of the biblical deadly sins as shown through gimmicky life.[2]

Another interpretation of the gesture between the homo and the demon suggests that the man is not merely tempted by wealth, but is offering it to Death as a bribe. Usury was not just a display of avarice as a sin that simply required the offender to confess and seek God for forgiveness internally, but demanded a specific type of repentance. According to the Church, reparations for amercement or reimbursement of monetary loss must be paid for this crime, just this is not something a miser on his deathbed would be able to practice. He could, however, rectify this at the moment of death past providing this indemnity in his will, though this particular human shows no intention of doing so.[ii]

The conflict depicted here casts doubt on who exactly the man is supposed to portray. A lombard would not worry virtually his afterlife or whatsoever façade of piety, as they were excommunicated from the Church, publicly shamed, and denied sacrament and Christian burial. That this homo is worried with at to the lowest degree an illusion of piety suggests that he may be a secret pawnbroker rather than an obvious lombard. This concept is strengthened past the setting; an official lombard in Augsburg or Bruges, both hubs of Northern Renaissance merchants and artists, would take a normal place of business, alike to a modest warehouse with a public facing function and storerooms to firm and organize goods. The human in Expiry and the Miser does not have that, shown instead with pawned items scattered in his room and locked in a trunk, which indicate that he may want to keep these items and his activities a secret.[two]

The Foreground [edit]

The meaning of the foreground is nevertheless unclear and debated past art historians, though they're reasonably certain virtually the symbolism inside the room. The Ars moriendi does non comprise a depiction of armor, or fifty-fifty pieces of information technology, and no other influence has satisfactorily explained their presence. Virtually hypotheses autumn into two schools of thought; the material, weapons, and armor are of symbolic significance, or they stand for the miser's former life, earlier Death came to have him.[3] Art historians' opinions accept seem to run the gamut of possibilities but in the 20th century lonely, which include the post-obit by no less than a dozen fine art historians:

- The objects represent an evil or malevolent force, the vanity of earthly goods, and the folly of earthly desires. They are placed in that location to be traps by the devil, to tempt you lot away from the Christian path, but their disregard in the scene shows that these earthly appurtenances cannot assist you lot against death.[eight] [7] The depiction of such inorganic objects to symbolize earthly vanity, transience or decay would become a genre in itself amid Flemish artists.[4] [v]

- They symbolize ability, potentially even anger, and how the miser came to exist wealthy.[9]

- The miser died as a knight; the weapons and armor are representative of his station.[10]

- The man might accept been a knight, but he was besides a dishonest steward and death has come for him.[11]

- Gilded is more than useful than a knight'due south courage and bravery, implied by placing the gold as a central subject field and office of the miser's final struggle while his knightly attire has been discarded in the foreground and outside the chief events of the scene.[12]

- The whole painting is satire about nobility and chivalry ,[half dozen] the items symbolic of the elite and their avarice.[thirteen]

- The carmine fabric could be evil, merely combined with the armor has also been interpreted as a symbol for St. Martin of Tours, who famously used his military sword to cut his cloak in half to give to a ragamuffin who lacked sufficient clothing for the winter. The architecture serves as a line betwixt Christian generosity, symbolized past St. Martin's items in the foreground, and greed, illustrated within the room.[14]

- The objects represent items that would have been pawned by knights, i.due east. jousting equipment, or textile goods from the poor, every bit an allusion to usury.[15] [2]

No single theory has been accepted as the most right, with art historians themselves admitting that none of the proposed explanations are entirely advisable or suitably thorough.[3] Schlüter and Vinken suggest an alternating source to their predecessors in the form of biblical texts themselves, namely Letter to the Ephesians 6:10-17, where St. Paul makes several mentions of the armor of God: "Put on the whole armor of God, that ye may be able to stand up against the while of the devil" (Ephesians 6:11); "Whereupon accept unto you lot the whole armor of God, that ye may be able to withstand in the evil twenty-four hour period, and having done all, to stand" (Ephesians six:13); "Stand therefore having your loins girt nigh with truth, and having on the breastplate of righteousness; And your feet shod with the preparation of the gospel of peace" (Ephesians 6:fourteen-15).

Throughout the following verses, St. Paul mentions specific pieces of armor, assigning certain aspects of Christianity to them; the helmet of conservancy, the shield of faith, the hauberk of justice, and the sword of spirit, which represents the discussion of God itself. There are as well other references to armor with assigned moral attributes in non-religious texts of the time menstruum, such every bit the pieces of Lancelot's armor representing a knight's duty to the Church, and chivalry.[3]

Physical Assay [edit]

The painting is believed to be the inside of the correct panel of a triptych, which has since been divided and no longer exists equally a whole. The other surviving portions of the triptych are The Send of Fools and Allegory of Gluttony and Lust, with The Wayfarer painted on the external right panel. It is one of the v fragmented triptychs past Bosch that accept survived.[16]

Several changes were made to the final painting every bit revealed by mod infrared analyses. A very faint remnant tin can exist seen on a loftier resolution photo, but the items are not clear. Originally, a flask, rosary, and tumblers were intended to be part of the collection of items in the foreground, but they were never painted. The scan also revealed that the miser's left mitt held a goblet while the right, every bit it appears today, is gesturing toward the coin bag. This has been interpreted as an offer to Death. The meaning of the alter is unclear, just it has been hypothesized that it could mean an offer of bribe; accept my money, don't take me, or an appeal to Expiry to allow the miser to take his riches with him when he dies.[2]

References [edit]

- ^ https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.41645.html National Gallery of Art. Retrieved 23 Oct 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f k h i j g Morganstern, Anne M. (1982). "The Pawns in Bosch'southward Death and the Miser". Studies in the History of Art. 12: 33–41 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d e f thou h Schlüter; Vinken, Lucy; Pierre (2000). "The foreground of Bosch's "Death and the miser"". Oud Holland. 114 (2/iv): 69–78 – via JSTOR.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors listing (link) - ^ a b Fiero, Gloria Thou. "The Humanistic Tradition Fifth Edition". 130

- ^ a b A Moral Tale, Webmuseum, Paris.

- ^ a b De Tolnay, Charles (1966). Hieronymus Bosch. New York: Reynal. ISBN9780517255254.

- ^ a b Manus & Wolff, pp. 17-8

- ^ de Tervarent, 1000. (1958). Attributs et symboles dans l'art-profane 1450-1600. Geneva. p. 34.

- ^ Walker, J. (1995). National Gallery of Art. New York. p. 166.

- ^ Reuterswärd, P. (1970). Hieronymus Bosch. Stockholm, Sweden. p. 266.

- ^ Chailley, J. (1978). "Jerome Bosch et ses symboles. Essai de decryptage". Académie Royale de Belgique, Mémoires de la Classe des Beaux-Arts. 15: 106–108.

- ^ Baldass, L. (1943). Hieronymus Bosch. Vienna. p. 236.

- ^ Cutler, D. (1969). "Bosch and the Narrenschiff: A problem in relationships". Art Bulletin. 51: 272–276.

- ^ Make-Philip, Lotte (1956). Bosch. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

- ^ Marijnissen, R.H. (1987). Hieronymus Bosch: The Complete Works. Random House Value Publishing. ISBN0517020386.

- ^ Jacobs, Lynn F. (Winter 2000). "The Triptychs of Hieronymus Bosch". The Sixteenth Century Periodical. 31 (4): 1009–1041 – via JSTOR.

Sources [edit]

- A Moral Tale, Webmuseum, Paris.

- Baldass, Fifty. Hieronymus Bosch. Vienna, 1943.

- Brand-Philip, Fifty. Bosch. New York, 1956.

- Bryant, Clifton D.; Peck, Dennis L. Encyclopedia of Expiry and the Man Experience. Los Angeles: SAGE, 2009. ISBN 9781412951784.

- Chailley, J. "Jerome Bosch et ses symboles. Essai de decryptage." Académie Royale de Belgique, Mémoires de la Classe des Beaux-Arts fifteen, I: 106-108

- Cutler, D. "Bosch and the Narrenschiff: A problem in relationships." Art Bulletin. 51: 272-276.

- Fiero, Gloria M. "The humanistic Tradition Fifth Edition". 130.

- Hand, John Oliver; Wolff, Martha. Early Netherlandish Painting. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-521-34016-0

- Jacobs, Lynn F. (Wintertime 2000). "The Triptychs of Hieronymus Bosch". The Sixteenth Century Periodical. 31, No. 4: 1009-1041.

- Linfert, Carl. Hieronymus Bosch. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1989. ISBN 9780810907195.

- Marijnissen, R. H. Hieronymus Bosch, The complete works. Antwerp, 1987.

- Morganstern, Anne Yard. (1982). "The Pawns in Bosch's Expiry and the Miser". Studies in the History of Art. 12: 33-41.

- Reuterswärd. Hieronymus Bosch. Stockholm, 1970.

- Schlüter, Lucy; Vinken, Pierre (2000). "The foreground of Bosch'due south 'Death and the Miser'". Oud Holland. 114, No. 2/four: 69-78.

- Silver, Larry (December 2001). "God in the Details: Bosch and the Judgment(s)". Art Bulletin. LXXXIII Number 4: 626-650.

- de Tervarent, Yard. Attributs et symboles dans l'art profane 1450-1600. Geneva, 1958, I: 34.

- de Tolnay, Charles. Hieronymus Bosch. New York: Reynal, 1966. ISBN 9780517255254.

- Walker, J. National Gallery of Fine art. New York, 1995.

- Wecker, Menachem (April 22 - May 5, 2016). "Largest-ever retrospective underscores Hieronymus Bosch's Catholic organized religion". National Catholic Reporter.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death_and_the_Miser

0 Response to "Beam of Light Coming From Persons Chest Fantasy Art"

Отправить комментарий